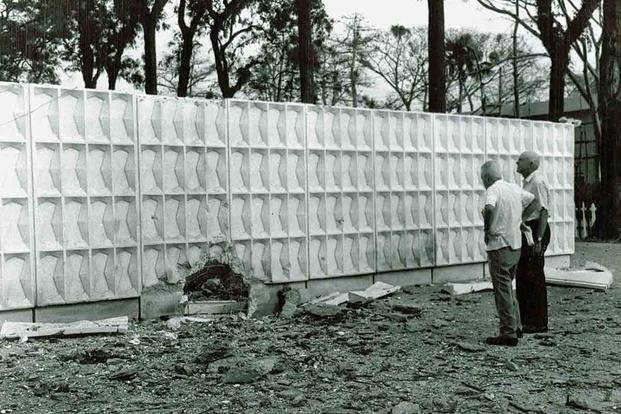

After the last American diplomats fled South Vietnam during the Fall of Saigon in April 1975, Associated Press reporters covering the communist takeover of the country's former capital city reported finding a bronze plaque that had been torn from the walls of the U.S. embassy there. It bore the names of four U.S. Army military policemen and one U.S. Marine; all five had died while securing the American embassy during the 1968 Tet Offensive.

The lone Marine, Cpl. James Conrad Marshall, was the first Marine security guard (MSG) to give his life while defending American embassy personnel. And he was not the last: According to the Marine Embassy Guard Association, 12 Marines have given their lives in defense of American property and personnel since Marshall made the ultimate sacrifice.

Marine security guards have a unique, important and coveted mission in the United States Marine Corps. They stand a lot of watches and, when called on, are also the police force for their small patch of American soil. These are typically pretty coveted postings, and often come complete with exceptional living quarters and amenities like maids, cooks and drivers. But don't let the sweet digs fool you into thinking it's not without its dangers.

It wasn't until 1948 that Marines became the official guards of U.S. diplomatic compounds. It makes sense; Marines not only provide excellent security for American embassies and consulates around the world, they are also a recognizable symbol of American military professionalism and power.

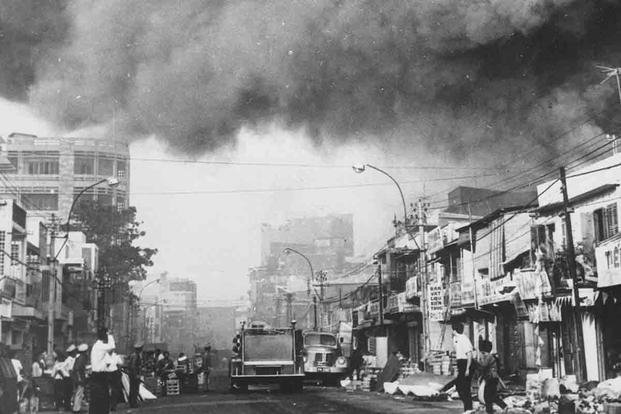

Marshall, an Alabama native, joined the Marine Corps as a warehouse clerk at age 21, but found himself among the MSG in Saigon on the morning of Jan. 31, 1968. That morning, North Vietnam and the Viet Cong launched an unprecedented, surprise escalation of the conflict, one American war planners had previously believed the North Vietnamese were incapable of mounting. Attacks came all across Vietnam, and Saigon was no different. The primary target in the capital was the American embassy.

Shortly after 2:30 am local time, U.S. Army soldiers guarding the embassy's front gate began to take fire from a nearby taxi. Those soldiers, Spc. Charles Daniel and Pfc. William E. Sebast, had just enough time to return fire and secure the gates before a large explosion rocked the compound's outer wall, killing them. Viet Cong sappers had blown a hole in the wall and were attempting to infiltrate the grounds and capture the embassy.

It would take six hours for American forces to regain control of the area, but the two soldiers' heroic last stand at the gate allowed time for Marine Sgt. Ronald Harper to cross the compound's grounds, then close and bolt the chancery's heavy wooden doors. Their call for help prompted the 716th Military Police Battalion to send a series of jeep patrols to check out the call. The first two patrols were ambushed, killing Army Sgt. Johnie B. Thomas and Spc. Owen E. Mebust.

Inside the embassy compound, events escalated quickly. Daniel and Sebast were able to respond to the blast, pouring fire into the hole created by the sappers and killing the team's leaders. They radioed for help, but before any could arrive, they were flanked and killed by the embassy's Vietnamese drivers, who attacked them from the parking lot in their rear and joined the VC.

Marine Sgt. Rudy A. Soto Jr. had also fired on the hole, but with only a shotgun and shooting from the roof of the chancery, his fire was ineffective. He, Sgt. Harper and Cpl. George Zahuranic were shut inside the chancery with six American civilians and two Vietnamese. They began arming themselves with whatever they could find, the most powerful of which were Beretta submachine guns, and waited for the Viet Cong to force their way in.

Meanwhile, the VC outside gathered on the grounds and exchanged fire with Marshall, who had climbed to the roof of one of the consular buildings in the compound and began laying fire on them with a submachine gun. This gave the defenders time to phone the rest of the MSG, who were at their barracks some five blocks away. The VC began firing at the wooden doors with rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) in an attempt to gain entry. Marshall was hit by a rocket fragment from one of these RPGs, He was shot and killed soon after.

Marines armed with shotguns and .38-caliber pistols made their way to the embassy as a quick reaction force, but with the gates still sealed, the Viet Cong's hole was the only way to gain entry to the building. They did not have the firepower to counter the VC's AK-47 assault rifles. In the end, the 716th Military Police Battalion would have to shoot off the locks to the compound's gates as the 101st Airborne Division landed on the roof of the chancery to sweep the building.

The Associated Press reporter who first found the memorial plaque in 1975 ultimately abandoned his effort to save it from the communists, and it ended up in a Vietnamese museum. The embassy, after briefly trying to reacquire the item from Vietnam decades later, commissioned a replica of the plaque, which was placed in the U.S. Embassy in Vietnam. It still memorializes the men who gave their lives to defend the embassy in the face of overwhelming odds.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.