Everything changed for the Military Assistance Command -- Vietnam (MACV), the U.S. military command sent to support the South Vietnamese regime, in 1968. MACV commander Army Gen. William Westmoreland, at the time the top U.S. general in Vietnam, was known for his perpetual positive outlook regarding the direction of the war, but even in his mind, things weren't going as well as expected.

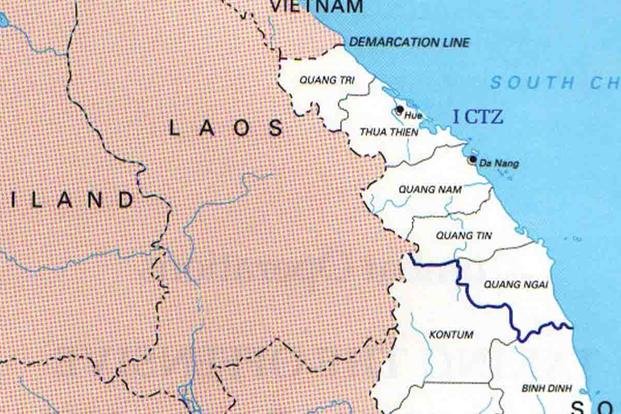

Days before the Tet Offensive would turn American sentiment against the war, the North Vietnamese Army attacked the combat base at Khe Sanh, a Marine Corps outpost in South Vietnam's Quang Tri Province just below the demilitarized zone that divided North and South. The fighting there would be some of the most brutal of the entire war, and Westmoreland worried the base and its Marines might be entirely overrun by the enemy. He requested low-yield tactical nuclear weapons be moved into the south, should he need them on short notice to prevent the fall of Khe Sanh.

Westmoreland had taken command of MACV in June 1964, to much fanfare from the leadership in Washington. Under his leadership, American involvement in South Vietnam would balloon from 16,000 troops to more than half a million. He believed inflicting irreplaceable casualties on the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and its guerrilla fighters, the Viet Cong (VC), was the key to winning. By the end of 1967, however, little had changed, no matter what Gen. Westmoreland said publicly.

"I am absolutely certain that, whereas in 1965 the enemy was winning, today he is certainly losing," he told the National Press Club in November 1967.

Westmoreland pinned his hopes on drawing the PAVN into pitched battles and defeating its forces with air power and artillery, areas where American troops in the country had the upper hand. By January 1968, he and much of the Army leadership believed a climactic battle would take place at Khe Sanh.

There were many reasons Khe Sanh was a natural target. It hosted the Army's Studies and Observations Group (SOG), a contingent of Special Forces soldiers who operated against the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Situated near the border with Laos, it also sat in the way of one of the enemy's major infiltration routes. Most importantly, all the available intelligence told the U.S. the North Vietnamese forces were moving at least two divisions, some 20,000-30,000 men, against the base.

While Washington and Saigon worried that Khe Sanh would become another Dien Bien Phu -- the disastrous pitched battle that cost France control of Vietnam in 1954 -- the ever-optimistic Westmoreland was openly confident that artillery, air power and helicopter resupply would win the day, convinced that superior firepower would finally overwhelm the enemy.

"After deliberate consideration, I ruled out abandoning Khe Sanh," Westmoreland would later say in his 1976 memoir, "A Soldier Reports." "To have done so would have been to cooperate with the enemy's grand design for seizing the two northern provinces and his constant efforts to carry the fight into populated areas."

In the days before the attack, Westmoreland reinforced Khe Sanh with two more Marine battalions, placed the Special Forces there under the command of III Marine Amphibious Force, moved a South Vietnamese Ranger battalion to the base, and shifted other resources toward the I Corps Tactical Zone in preparation to advance on Khe Sanh, if necessary. By the end of January, more than half of the U.S. combat battalions in South Vietnam were in the I Corps zone.

On Jan. 21, 1968, the communists finally began their attack on Khe Sanh. After they blew up the Marines' ammunition stores, the Air Force began launching B-52 attacks against the PAVN and against sites in Laos. Air Force cargo planes and helicopters also began an aerial resupply campaign while the Marine Corps began planning an amphibious invasion of North Vietnam as a potential diversion. Westmoreland was determined not to lose this battle.

Then, in the early morning hours of Jan. 30, an estimated 80,000 PAVN and Viet Cong troops struck more than 100 towns and cities across South Vietnam in a massive, coordinated attack. The Tet Offensive had begun, and the masses of troops set to support Khe Sanh were suddenly needed elsewhere, further threatening the American grip on the combat base. A relief expedition, codenamed Pegasus, would not advance on Khe Sanh until March 1968.

"No single battlefield event in Vietnam elicited more public disparagement of my conduct during the Vietnam War than did my decision in early 1968 to stand and fight at Khe Sanh," Westmoreland wrote in his memoir.

Perhaps nothing is more indicative of Westmoreland's resolve at Khe Sanh than "Fracture Jaw," a plan he put forward to Adm. U.S. Grant Sharp Jr., the commander in chief, Pacific. On Jan. 24, 1968, Westmoreland asked Sharp to move tactical nuclear weapons into northern Quang Tri province as a last-ditch effort to prevent North Vietnamese forces from capturing Khe Sanh. The weapons would be moved by sea from Guam under the utmost secrecy and deployed in the mountains of South Vietnam around Khe Sanh.

Upon hearing the plan was set in motion, President Lyndon B. Johnson was livid and ordered Westmoreland to shut it down. Johnson was concerned that use of a nuclear weapon would draw China into the war. The president did not trust the generals in Vietnam and did not want them dictating the overall course of the war. Fracture Jaw was dead, but the fighting at Khe Sanh would continue until July of that year.

The Tet Offensive was a tactical disaster for the North Vietnamese. It all but destroyed the Viet Cong as a fighting force, and the North failed to hold onto any gains it made during the offensive. Estimates of communist casualties vary between 60,000 to 95,000 killed. In the end, both sides claimed victory at Khe Sanh. The Vietnamese believe they forced a U.S. withdrawal under fire while the Americans say they abandoned the base because it was no longer strategically necessary.

In June 1968, Westmoreland was sent to Washington to serve as chief of staff of the U.S. Army, replaced in Vietnam by Gen. Creighton Abrams. For the rest of his life, Westmoreland believed the Tet Offensive was a diversion and the real goal for the communists was Khe Sanh. Vietnam has never officially confirmed which was the goal and which was the diversion, but the North Vietnamese commander commented on the battle after the war

"Khe Sanh was not that important to us," said Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap, according to the book "Tet 1968: Understanding the Surprise." "It was the focus of attention in the United States because their prestige was at stake, but to us, it was part of the greater battle that would begin after Tet. It was only a diversion, but one to be exploited if we could cause many casualties and win a big victory."

Westmoreland remained steadfast in his decisions.

"Khe Sanh will stand in history, I am convinced, as a classic example of how to defeat a numerically superior besieging force by co-ordinated application of firepower," he wrote.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.